In 1990 Peter Maag (1919–2001) returned to the Gran Teatro del Liceo in Lisbon for a run of Così fan tutte, an opera he had been directing for over 40 years. He raised a few eyebrows when he asked for an orchestra of only 26 players. ‘If there is more,’ he explained, ‘Mozart vanishes.’ Mozart, or at least his spirit, is surely alive and well in the recordings he made for Decca almost throughout his career, and which are gathered together for the first time in this set.

The story begins in Geneva, in October 1950, with Mozart’s sunniest mature symphony, the A major KV 201. Writing in the April 1951 issue of Gramophone, Lionel Salter cut to the chase: ‘The conductor, a name new to me, has the right Mozartian spirit.’ We may echo Salter’s judgment in hearing once again the unobtrusive rightness of the tempi, in the unexaggerated accents, which support and colour the melody without covering it in a thick blanket of legato, in the quick feet of the Suisse Romande orchestra’s Minuet style, in the wind-favoured balances which allow for the liveliest dialogue between sections, and in the cut and dash of the finale which breathes the air of opera buffa as any successful performance of the symphony should.

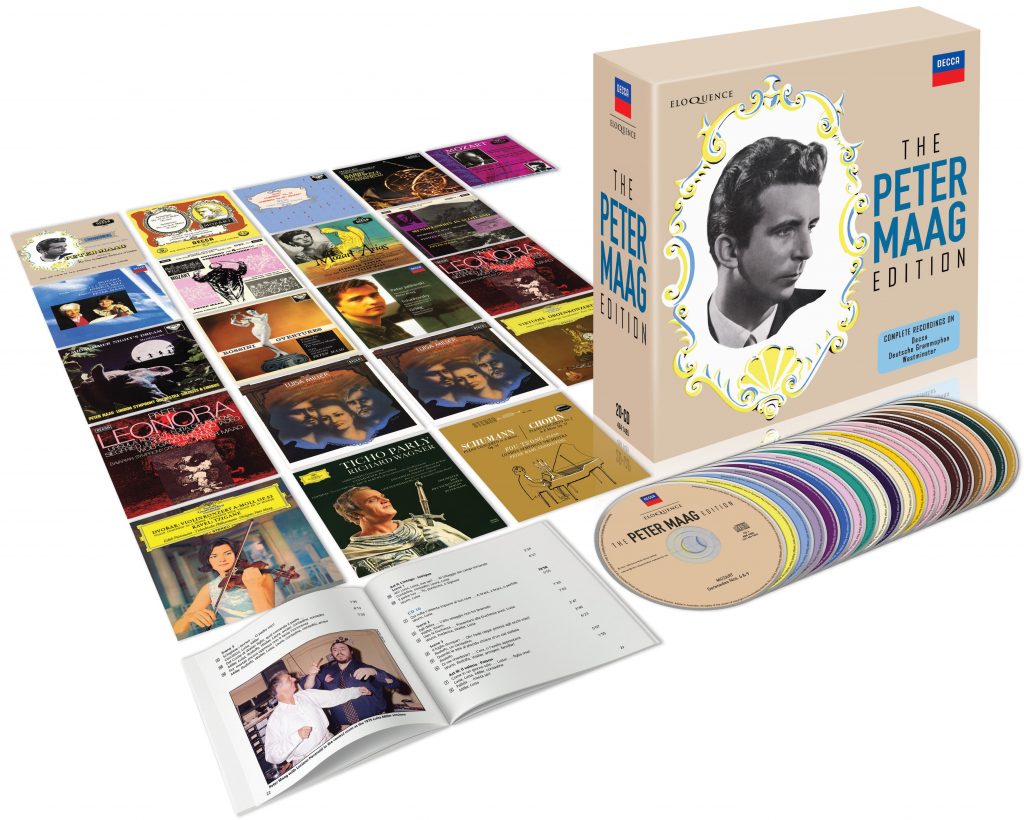

The Peter Maag Edition 20-CD box set is out now on Eloquence Classics

Many conductors have steered clear of Mozart early in their career, only too aware of the narrow but perilous gap between perfection and disappointment, also of the weight of history pressing down upon them from previous, distinguished interpreters. Yet this recording of the Symphony No. 29 proved to be no fluke. It was quickly succeeded the following spring by two more symphonies, Nos. 28 and 34. Indeed Maag’s first seven Decca recordings were exclusively dedicated to Mozart. Reviewing the two rival versions available of Mozart’s ‘Posthorn’ Serenade in October 1953, the critic of High Fidelity set Maag against his exact contemporary, Jonathan Sternberg. ‘Mr. Maag has a lither beat, a more confident control and subtler responses than Mr. Sternberg, sturdy and vehement. The former has the greater experience and the records show it.’

To trace the source for this experience, or the illusion of it, we might return to Maag’s childhood, growing up in the Swiss town of St. Gallen. He was born there on 10 May 1919. His father Otto (1885–1965) was a former Lutheran pastor who lost his faith after World War I, became a professor of philosophy and moonlighted as a music critic for the Basel newspapers. His mother Nelly played second violin in the Capet Quartet. Looking further back, Nelly’s grandmother had taken piano lessons from Clara Schumann, while among his great-uncles was the conductor Fritz Steinbach, whose scores preserve a unique working and personal relationship with Brahms.

Through Otto’s connections, the teenage Maag was introduced to Arturo Toscanini at the 1937 Salzburg Festival. Maag’s own marked-up score of Die Zauberflöte is dated 19 August 1937, evidently acquired while Toscanini was directing the opera with a cast (preserved for posterity on a broadcast) from Mozartian nirvana: Helge Roswaenge as Tamino, Jarmila Novotná as Pamina, Willi Domgraf-Fassbaender as Papageno.

Maag’s own musical talents at this point in his life were channelled through the piano. Having studied music at the universities of Zurich and Geneva, he took masterclasses with Alfred Cortot at the École Normale in Paris. There is even an extant fragment (would that there was more) of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto with Maag at the piano and Cortot on the podium. It was in this capacity that Maag made the decisive musical encounter of his life, with Toscanini’s bitter rival and musical antipode, Wilhelm Furtwängler. They performed Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto together, and evidently struck up a rapport, engendered by a shared outlook and broad humanistic education, Maag having studied theology with Karl Barth and written a doctorate on Spinoza. At a post-concert dinner, Maag often liked to remember in interview, Furtwängler asked him: ‘Do you conduct?’ When the young pianist demurred, the conductor pressed him: ‘Why not? I watched you during the concert, looking at the orchestra more than the keyboard. You gave them more entries than I did!’

‘You must start in a very small theatre,’ Furtwängler told Maag, ‘and take gradual steps, from substitute conductor to repetiteur, to chorus master and finally to music director. It must be a very small theatre that will give you the opportunity to conduct.’ The advice – a classic career path for young conductors – was duly followed, and Maag found a job at the theatre in the Swiss town of Biel-Solothurn, where he arranged and conducted the likes of Tannhäuser and Don Carlos for an orchestra of 22 and a similarly sized chorus.

At the end of his first season with the Solothurn theatre in April 1944, Maag joined Furtwängler as an assistant through the summer months. ‘I travelled with him, I observed him and I worked hard to understand how he succeeded in transforming the colours of an orchestra through his person. I discovered that it was not a gesture or a movement which inspired the musicians but his eyes. Obviously when Furtwängler was faced with an orchestra that was not accustomed to his peculiar way of conducting, initially the musicians were troubled by his kind of trembling beat which was difficult to locate, but after a few minutes the result was miraculously clean and the whole orchestra was subdued by his eyes.’

PHOTO: DECCA

PHOTO: © TRUDE FLEISCHMANN / DG ARCHIVE

In 1946 Maag left Solothurn for Geneva, working as an assistant to Ernest Ansermet, and thus the Suisse Romande orchestra had become quite familiar with his style by the time of their first Decca recordings together. In fact Maag’s first recording of the Symphony No. 34 was initially coupled on LP with Ansermet conducting the Prague. With the London Symphony Orchestra he then set down his own take on the Prague as well as the overture-like symphony KV 318, Mozart’s late German dances, a lovely pair of serenades, and wind concertos featuring the LSO’s principals at their most mellifluous. By then he had become known across Europe and farther afield as a Mozart specialist: no small accolade in itself, but one that hardly does justice to a repertoire that always ranged from the Baroque to the tonal end of contemporary music, taking pleasure in unearthing rarities as well as polishing masterpieces, especially in his work with the Italian radio orchestras (Hugo Wolf’s Christnacht cantata in Turin in 1961, the blood-and-thunder Piano Concerto by Emilia Gubitosi in Rome three years later).

Plans for a stereo Suisse Romande remake of the 1951 ‘Posthorn’ Serenade fell through, but Decca had at least taken advantage of Maag’s operatic expertise with a 1952 ‘medium-play’ 10-inch LP of Mozart arias with the rising Italian bass Fernando Corena, and two years before his Covent Garden debut in Die Zauberflöte, the Royal Opera Chorus were on hand at Kingsway Hall in February 1957 for a recording of the complete incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Maag’s light touch in Mozart transferred itself ideally to Mendelssohn at a time when the composer’s orchestral music (beyond the ‘Italian’ Symphony and Hebrides Overture) was still undervalued. This album (also held in high esteem by its conductor) and the Scottish Symphony recorded in 1960 quickly attained reference status in the early Decca stereo discography and have hardly fallen out of circulation since then.

Maag’s career had moved rapidly upwards throughout the 1950s, charted by his increasingly prestigious operatic posts: from Düsseldorf (1952–55) to Bonn (1955–59) and then music director of the Netherlands Opera in Amsterdam, taking in Mozartian debuts with not only the Royal Opera but also Glyndebourne (Le nozze di Figaro, 1959), the Lyric Opera of Chicago (Così again, 1961) and later the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires (Così, 1967). However, the Amsterdam appointment came to a premature end when he walked out two months after taking up the post in September 1960: ‘I am profoundly dissatisfied with Amsterdam’s rehearsal facilities,’ he complained in High Fidelity, ‘the general disciplinary arrangements, and the interference in artistic matters by the musicians’ and “house” unions … I cannot tell you how glad I am to get away.’

Fearing burnout, Maag cancelled all engagements early in 1962: ‘I had the feeling that I was not performing as I should. I was feeling things that had nothing to do with the original feelings that made me choose music for my life. I went on to the podium and thought not of music, but of myself, of success, of ambition.’ In search of a centre to his life, he took himself off firstly to the monks of Mount Athos, and then the Greek Orthodox Patriarch in Istanbul, who recommended a Buddhist monastery near Hong Kong. Shortly before flying east, however, Maag led the LSO in sessions for the American Westminster label, accompanying the Chinese pianist Fou Ts’ong for an album of concertos by Chopin and Grieg.

Not dissimilarly to his shorter-lived contemporaries Ferenc Fricsay and Kirill Kondrashin, Maag’s temperament could accommodate the role of concerto accompanist with a natural éclat, neither subduing his authority nor imposing it on the musical personality of his soloists. The Westminster engineering in Walthamstow Town Hall does few favours to the piano tone, and the sleeve-note for its first issue in 1963 talked about Fou Ts’ong as ‘Rubinstein’s successor’ with premature enthusiasm, eight years after his career was launched at the 1955 Chopin Competition in Warsaw, but conductor and pianist establish a particularly genial rapport in the Schumann. Excerpts of this recording were used on the soundtrack of Madame Sousatzka, John Schlesinger’s 1988 movie about a Russian piano teacher (with Shirley MacLaine in the title role), but the complete album last saw the light of day in 1980; with this set, it receives a first transfer to CD.

Having planned a retreat of three months, Maag extended his sabbatical at the monastery, though not for the two years he claimed in later interviews. ‘I felt I had to go there,’ he said later, ‘far away from my usual life and my travelling from one continent to the other. I said to myself that such a life had nothing to do with music and with theology and that I was just becoming a businessman. So I went to the monastery to cleanse myself, to rediscover the real spirit of music and not to become victim to routine. When I returned after the break, however, people had forgotten me. My sudden dropping of engagements was not understood and even condemned. I had to start again from the beginning.’

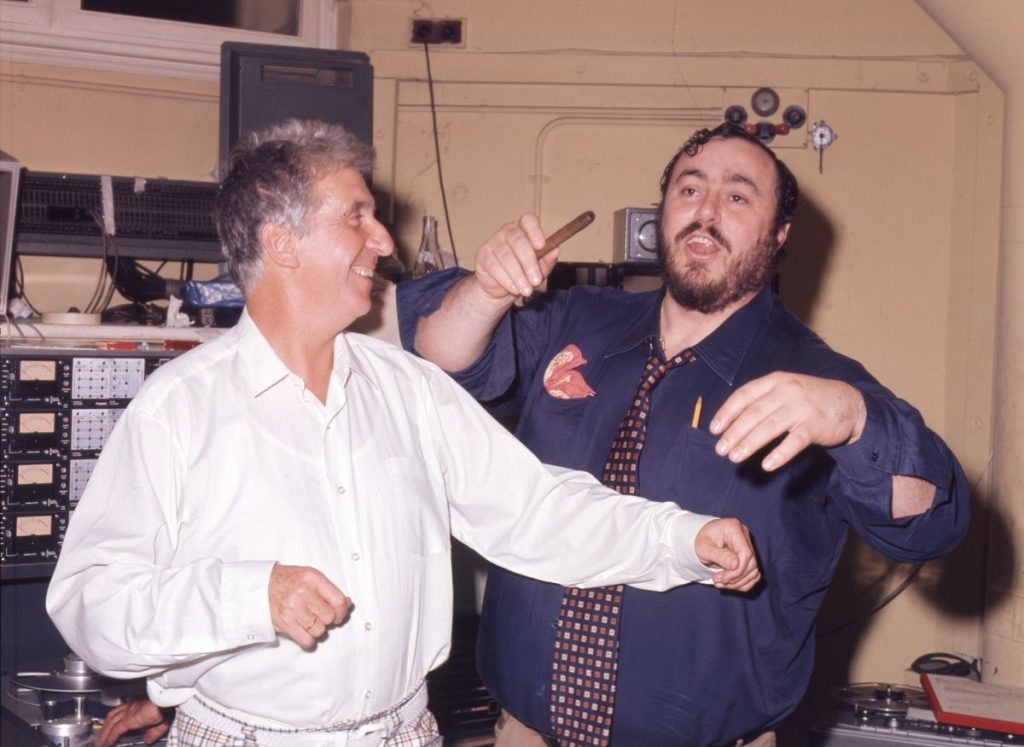

For whatever reason, Maag’s sabbatical also marked a hiatus in his activity for Decca. Having completed the Mozart horn concertos with Barry Tuckwell and the LSO in 1961, he did not return to Kingsway Hall for fourteen years. When he did so in June 1975, however, it was trailing in the wake of the world’s hottest operatic property, Luciano Pavarotti, for a complete recording of Verdi’s least-familiar treatment of Schiller, Luisa Miller. Conductor and tenor had worked on the piece together for a Turin radio broadcast performance in December 1974, while the other leads had featured in a recent Metropolitan Opera staging, and the results must have impressed the company’s artist and repertoire chiefs.

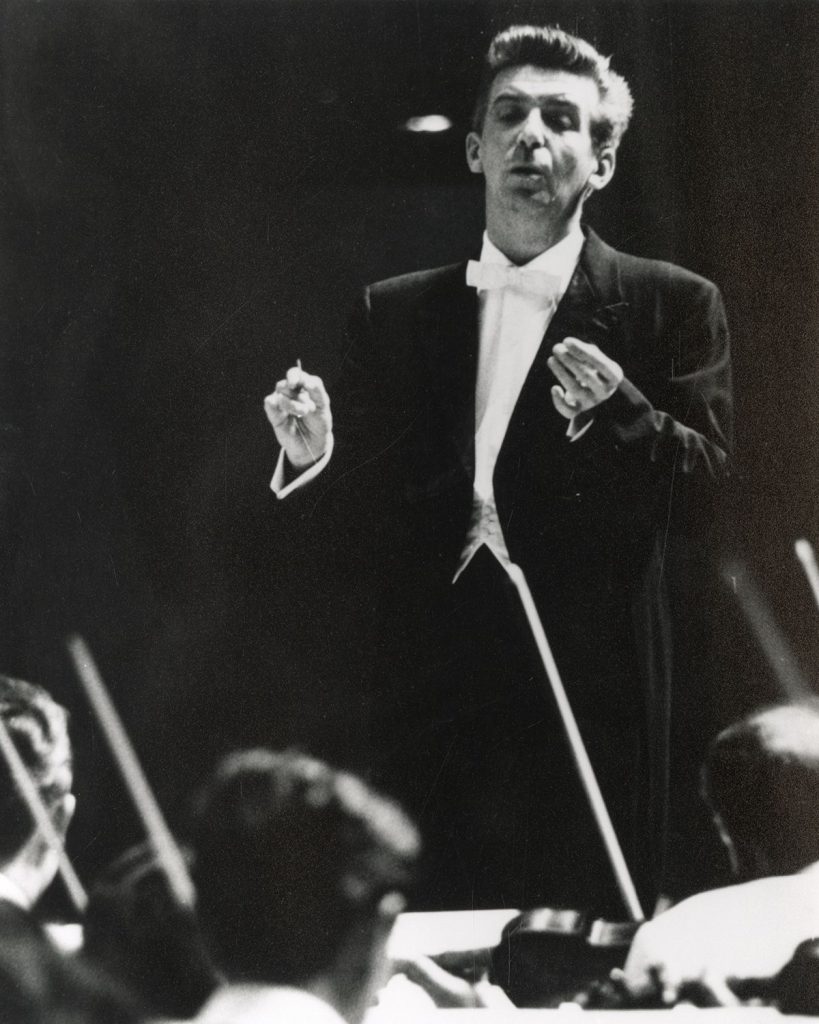

For all his philosophical tendencies, Maag was a livewire on the podium, with facial expressions as mobile as his gestures, and a left hand in command of the most subtle suggestions of timbre, as an NHK film of Schubert’s ‘Great’ C major Symphony confirms. The influence of Furtwängler ran deep, but so did the experience of making things work in the pit, from Solothurn onwards. Maag never suffered fools or idlers gladly, but music-making was always a collaborative endeavour, and his shaping of the complex third act of Luisa Miller is most sensitively moulded to the particular talents of his singers.

In 1973, Maag had come to a second accommodation with opera-house drudgery as music director in Parma. It was while researching the theatre’s archives there that he turned up the score to a ‘rescue opera’ which Fernando Paer had written to the same scenario by Bouilly as Beethoven in his protracted composition of Leonora/Fidelio. Beethoven admired Paer’s Leonora and, as Maag contended when his Decca recording was released in the summer of 1979, even if it remains in the shadows of Fidelio, ‘as a dramatic whole … it could be considered more successful … It’s more Italianate, more brilliant in the writing, but I find it a happy marriage between German depth and Italian lyricism and virtuosity.’

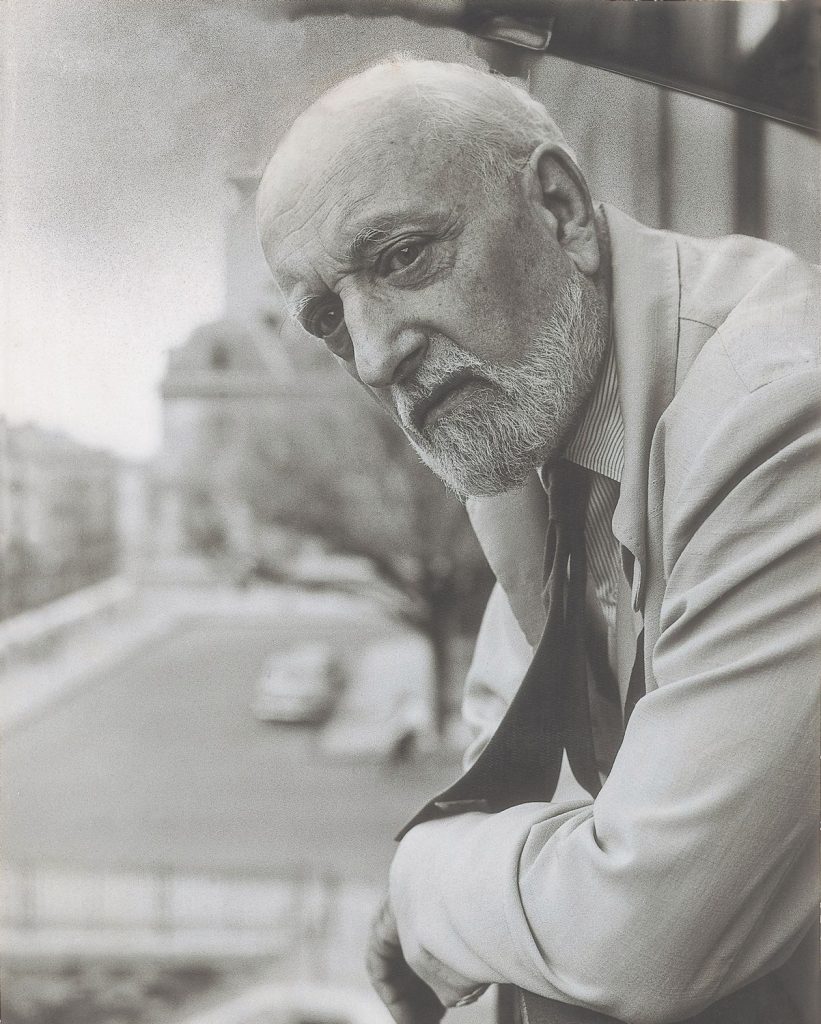

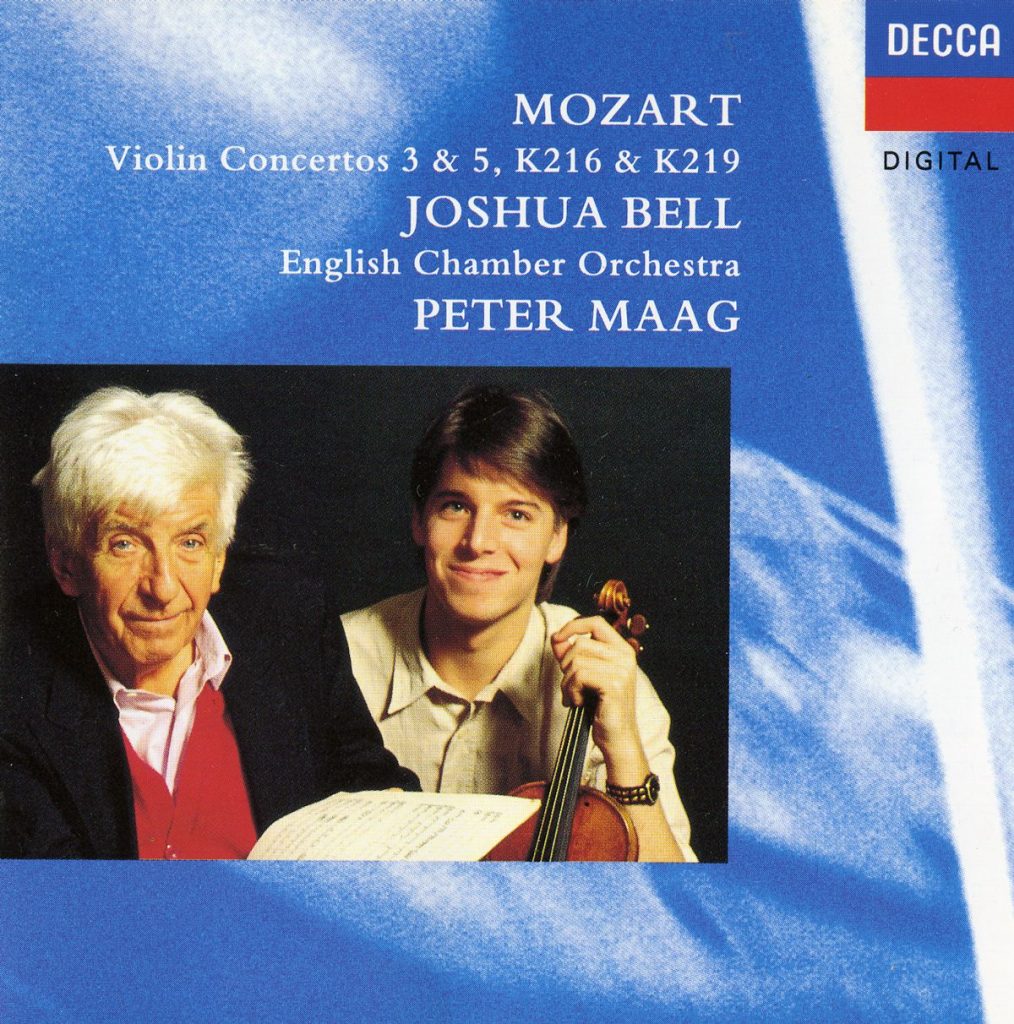

Maag was still fulminating against the unrewarding nature of opera-house jobs in the same Gramophone interview – ‘too much of a problem with politics and unions at the expense of musical standards’ – and by then he had begun to centre his work closer to home, taking operatic guest engagements in houses where he had an established relationship such as Lisbon and Madrid, and becoming chief conductor of the Bern Symphony Orchestra (1984–91) and the Orchestra di Padova e del Veneto (1983–2001). However, he retained a fundamental generosity of spirit even through the Indian summer of his career, when other conductors of similar seniority tend to put on a grand manner. Thus he made a pair of return visits to London for Decca in order to accompany soloists at the very start of their careers, the violinist Joshua Bell and the pianist Peter Jablonski.

‘In the early 90s I was invited to play with the Bern SO and another conductor,’ remembers Jablonski. ‘I think Maag may have heard about it, because in 1992 I was invited to play the Grieg with him in Washington with the NSO – and we had the kind of reviews you could have written yourself! So when I was invited to record the Grieg by Decca, I suggested the conductor. I was very young, in my early twenties, but when we played through the piece in his dressing room I found a human rapport that I had not experienced with other maestros of the same age and distinction, who could be very uncomfortable to be around.’

More than a quarter of a century on from the sessions at Walthamstow Assembly Hall, Jablonski vividly recalls Maag at work, in a fitting envoi to his Decca career: ‘In the Grieg, he wanted the second theme of the first movement to sound like a combination of Chanel No. 5 and a Michelin tyre. I hadn’t heard conductors talk like that before! He was concerned with sound and with shape, he talked about long phrases. And it did make a difference – the Philharmonia players showed him a lot of respect, and they knew there was someone special standing in front of them. There was no question of who was in charge, but he was particularly nice. He was an incredibly nice, gentle maestro.’