It was common from medieval times to think of the Arts as female; in most European languages the words for them are feminine, and in pictures too they were represented as heavenly ladies, each carrying some appropriate object, and often attended by the male figures of her most famous earthly servants.

The frontispiece chosen by Dowland’s publisher for the First Booke of Songs is typical, showing as it does the ladies Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy and Music, attended by Strabo, Ptolemy and Polybius. These four ladies were the ‘Quadrivium’ or Four Ways to enlightenment, and, together with the ‘Trivium’ or Three Ways of Grammar, Rhetoric and Dialectic, made up the seven Liberal Arts that were the basis of any gentleman’s education.

It may surprise us to see Music grouped with the Number Sciences. The harmonies and proportions of music provided for man a taste of the divine principle of Creation, the perfect system of balance and harmony that made up the song of the universe. This ‘musica divina’ or ‘musica mundana’ was too subtle for human ears to comprehend; as Shakespeare put it:

Such harmony is in immortal souls;

But, whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it.

(The Merchant of Venice, Act V Scene 1)

The music that man could make was of two kinds: ‘musica humana’ , his own song of praise, and ‘musica instrumentalis’, his playing of instruments. Both had the clear function of – harmony of God, and of refining his senses the better to hear it.

Robert Jones’s If in this flesh echoes very closely Shakespeare’s imagery, and represents the soul arising from the ‘indrenching’ flesh to retrieve her former glory and join with the song of the angels.

In Come let us sound Campion takes us further back, as it were, to the process by which man is to escape the flesh. He celebrates God the ‘Author of numbers, that hath all the world in harmonie framed’ and asks the Holy Ghost to rescue the soul from earthly darkness. The work is an experiment in three of Campion’s skills – music, poetry and Classical Studies. In the manner of his French contemporaries, Campion has set his poem in the Greek ‘Sapphic’ metre as exactly as possible, with long and short notes to match the metric syllables. The result has a flowing eloquence unaffected by the absence of a regular tactus.

The image of darkness and light reappears not surprisingly in Dowland’s In this trembling shadow, also on the theme of music in God’s praise. In fact this song is one of his most mellow and optimistic, as though the darkness in man, so much a preoccupation of Dowland’s earlier work, is finally seen to be contained by the power of God.

All these songs take for granted that one of man’s main objects is to sing joyfully in God’s praise; in this he shows his affinity with the angels who exist for no other purpose. But man’s other features, which tie him firmly to earth, are seen as cause for sorrow. In this too music has a role, for what can give finer expression to grief? Two songs treat of this, with essentially the same text. Dowland’s I saw my Lady weepe and Morley’s I saw my Ladye weeping, both published in 1600, have close thematic resemblances, such that one can only assume some parody work. The fact that Dowland placed his setting first in his Second Booke, printed all three verses and dedicated the song to Anthony Holborne (who had already paid tribute in print to Dowland’s supremacy in melancholic music) suggests perhaps that he was more personally involved in the conceit.

Morley’s textual variations are small, though interesting: ‘as winnes mennes heartes’ may seem to us ungrammatical in context, but it is clearly written out twice and the long rest for the singer that follows it goes better after that self-contained image than it would after the other version ‘as winnes more heartes’ where the sense requires completion. Both songs are clear, however, in declaring the supremacy of Music’s woe over the enticing parts of the Mirthful ditty.

In the Elizabethan as in many other ears of music, the plaint and the elegy were much favoured, and generally represented the highest levels of artistic achievement. So in Pilkington’s elegy Come all ye Mr. Thomas Leighton’s musical colleagues are required to give of their finest art:

Let these accords which notes distinguisht frame,

Serve for memoriall to sweet Leighton’s name…

But if music is a means for man to glimpse the joy of the angels, she must therefore have the power to assuage sorrow and comfort the ‘heavy sprite’. Where gryping griefs expresses this with disarming simplicity; the ‘gryping griefs’ and ‘doleful dumps’ of the human condition, here painted in curious chromatic turns of melody, are dispelled by Music’s ‘silver sound’ and ‘pleasant sweet delights’. Pilkington’s Rest sweet Nimphs shows us Music’s soothing guise in the lullaby; this is something of a luxury version, sung by a figure with a lute, and lulling several sweet nymphs to rest with dreams of their loves, but even Pilkington allows us a simple, catchy refrain.

The ‘Lady Musick’ was portrayed over the centuries with a variety of identifying features. In a relief from Chartres Cathedral she plays the bells, symbolic of perfect mathematical harmony; often she was shown sharing the marvels of the monochord with Pythagoras; in Baldung’s painting she has a viol, and in several depictions she sits at the organ, prefiguring St. Cecilia by some centuries. By the High Renaissance, though, her most common instrument was the lute, so much so that to portray an actual Renaissance lady with a lute was to pay her the compliment of symbolising her as a ‘Lady Musick on earth’. Even Queen Elizabeth, mainly known for her skill on the virginals, appears with a lute in a miniature by Nicholas Hilliard.

At the same time we find poems celebrating the skill and power of a ‘fair singer’ who with her song to the lute can inspire and move the listener beyond himself. In When to her lute , the lady in question can play on the poet’s heart-strings just as easily as she plucks those of her lute. (Even the ‘heart-string’ idea has a long pedigree: the Arab ‘ud’ , ancestor of the lute, traditionally had a string for each of the humours, whose balance in the human body was so crucial for physical and mental health. Doubtless a well-chosen piece of music could be as efficacious for the listener’s condition as a draught from the apothecary.)

Musick deare sollace is a rather more opulent treatment of the ‘fair singer’, but its heavy allusive style repays attention and the result is rich but enjoyable. Finest of all in this field is ‘Like as the lute delights’ , a happy combination of the talents of brothers Samuel and John Danyel. Samuel’s Muse also strikes on his heart-strings but is undoubtedly a more heavenly source of inspiration than Corinna – his sonnet celebrates her as the ‘sweetest ground’ of all his efforts, and, as if to illustrate this, the wealth of musical allusions is marvellously controlled so that not a word or image is wasted. John rose to the challenge of his brother’s magnificent poem, having the audacity even to alter it in places for his purpose, and produced a masterpiece. On first hearing one can enjoy the formal grace and satisfying shape of his setting, and be arrested by the more obvious effects, such as the expressive silence after the word ‘touch’, the ‘pleasing relish’ (to an Elizabethan this was a musical ornament, and Danyel writes in a delightful example at this point) or the ‘wailing descant’, But this last, we are told, is ‘on the sweetest ground’, and yet by the time we hear of it, it is already over; only repeated listening will reveal the delightfully simple answer to this mystery, and at the same time uncover a host of other masterly responses to the text.

In Bartlett’s trilogy which closes the record, fourteen ‘fair singers’ take us from sadness, ‘Surcharged with discontent’ , through a range of exuberant musical delights, to a cheerful conclusion – all of them birds, but surely the ‘Lady Musick’ would not disdain such company, nor object to the refrain ‘Of straines so sweete, sweete birdes deprive us never’.

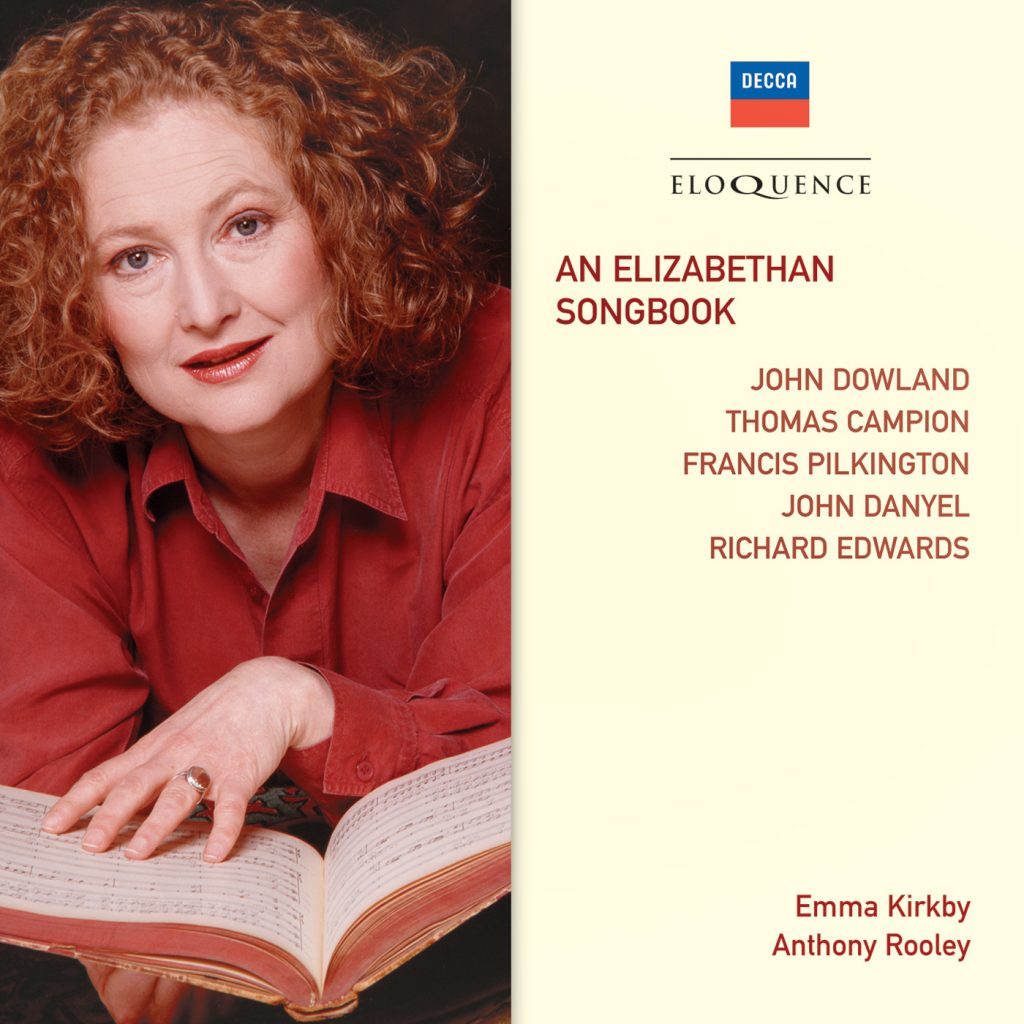

Emma Kirkby

RICHARD EDWARDS: Where grypinge griefs

THOMAS CAMPION: Come let us sound

JOHN DOWLAND: In this trembling shadow

JOHN DANYEL: Like as the lute delights

JOHN DOWLAND: I saw my Ladye weepe

FRANCIS PILKINGTON: Rest sweet Nimphs

THOMAS CAMPION: When to her Lute

FRANCIS PILKINGTON: Musick deare sollace

THOMAS MORLEY: I saw my Ladye weeping

ROBERT JONES: If in this flesh

FRANCIS PILKINGTON: Come all ye

JOHN BARTLETT: Sweete birdes deprive us never

Emma Kirkby, soprano

Anthony Rooley, lute

Recording producer: Peter Wadland

Recording engineer: Martin Haskell

Recording location: Decca Studios, West Hampstead, London, June 1978

‘Affecting treatment of the intimate lute songs of the Elizabethans’ Fanfare

‘This a wonderful disc … Kirkby conveys a wonderful sweetness. Her intonation is absolutely spot-on, her enunciation is perfect … The songs are all delightful, and Kirkby captures the nuances of the texts brilliantly. Highly recommended’ MusicWeb