Brahms’ Violin Concerto comes from the same period as his Second Symphony, with which, in sprit, it has much in common. A similar serenity and insistence on carefully balanced form pervades both works. The first performance of the work was given in Leipzig on New Year’s Day 1879. The concerto is in three movements and, as one would expect from Brahms, it shows little trace of the Romantic tendencies towards the rhapsodic ‘free’ form that was the trend during the mid-nineteenth century. Instead it is constructed firmly on the admittedly flexible principles of the Classical concerto, although its musical content – the style and the treatment of its themes – is clearly Romantic.

The first movement opens with a broad orchestral exposition of all but one of the themes that are to take part in the movement. The subsequent development of these themes lies chiefly in the hands of the soloists. The main theme – the extended melody with which the concerto opens – is of particular importance, since in the course of the movement it is treated both as a whole and in sections, each of its three main phrases being subsequently used as an individual entity. The second subject likewise consists of a group of ideas, although their essentially flowing melodic natures make it difficult, and perhaps unnecessary, to separate them.

The Adagio is an extraordinary movement. Despite its apparent simplicity and the almost continuous nature of its melody, it is a highly organised structure – a profound meditation on the beautiful tune introduced at the outset by the oboe and woodwind group. The various fragments and phrases of this tune are taken over by the solo violin, and from these phrases Brahms builds a movement of intense, but restrained, emotion.

The finale is a rondo. The main theme is introduced at once by the solo violin and is perhaps the ghost of some Hungarian melody, although it is a very jovial and Brahmsian ghost. A wealth of melody appears in the movement, culminating at last in a final version of the main theme, transformed into a march rhythm and even more energetic than befor

Brahms was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Philosophy by the University of Breslau in 1879; for the occasion, he wrote what musically is possibly his least ‘academic’ piece, consisting of mostly a pot-pourri of traditional student songs. On its own, the work gives a rather one-sided view of Brahms; it was premiered in Breslau alongside the general gloom of the ‘Tragic Overture’ (Op. 81), giving the audience a more complete picture. The opening music is Brahms’ own; the songs he quotes include (on the trumpets near the beginning) ‘Wir hatten gebauet ein staatliches Haus’, and (in the triumphant coda) ‘Gaudeamus igitur’.

In pre-jukebox days, a healthy supply of silly songs was an essential accompaniment to the consumption of medically inadvisable quantities of beer; into this category falls the song ‘Was kommit dort von de Höh’, quoted in jocular fashion on two bassoons. In full, it has twenty verses, each describing something unexpected as ‘leathery’. Thus the first verse: ‘Was kommit dort von der Höh’, was kommit dort von der Höh’?’ (What is that coming from the [leathery] sky?). If anything, perhaps students off duty are less silly nowadays, although the margin would be slim.

The ‘Tragic Overture’ is an oddity in Brahms’ orchestral work – a grittily minor-keyed symphonic first movement with no symphony to follow it. the British musicologist Donald Francis Tovey indeed maintained that this was Brahms’s finest symphonic first movement – but musicologists are contrary creatures.

Brahms is often pigeonholed as an ‘autumnal’ composer – as Michael Steinberg has put it, ‘this incomparable master of greys and browns’. This is not entirely accurate: his output is overwhelmingly dominated, even at the end of his life, with the same fierce, youthful passions with which, as Schumann unforgettably put it, he sprang ‘fully-armed like Minerva from the head of Jupiter’. It is perhaps fair in considering his whole output in historical context – as a composer who continued to use a post-Beethovenian language after Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner and even Bruckner had been and gone – but the actual works to which the stereotype best applies are, paradoxically, perhaps his least-performed.

Among them is the ‘Alto Rhapsody’. This sets a fragment from ‘Harz Journey in Winter’: a poem arising out of Goethe’s visit in 1777 to the Harz mountains, partly to visit a theology student suffering from depression induced by reading one of his works. The poem sets a solitary misanthrope’s feelings in stark relief against the general happiness of the mountains; the opening of its text translates as: ‘But who is this off the path? His track is lost in the undergrowth, the bushes close behind him, the trampled grass springs back, the wasteland swallows him up’.

Brahms’s work in symphonic forms is mostly conceived along highly traditional lines; that this is quite deliberate is well demonstrated here. The entire opening section is strikingly adventurous in both its harmony and expressive content – in particular, the line ‘Die Öde verschlingt ihn’ (the wasteland swallows him up) is as evocative of emptiness as anything his contemporaries, Wagner included, could have imagined.

The second section’s text reads in part ‘who shall heal the pains of him whose balm has turned to poison, who drank hatred of mankind from the abundance of love?’ The chorus enters for the final section: ‘if any sound from your psaltery can reach his ear, O father of love, refresh his heart!’ The psaltery is heard in pizzicato strings and the ending is an Amen in all but word.

To those who know only his instrumental music, or even his Lieder, it seems astonishing that Brahms ever considered writing an opera; to those who know this work, it seems incredible that he never wrote one. An even greater surprise is that Brahms composed the work on the occasion of the wedding of Clara Schumann’s daughter; it is unquestionably more a reflection on his own solitary state than an epithalamion proper.

Carl Rosman

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77*

Academic Festival Overture

Tragic Overture

Rhapsody for alto, chorus & orchestra, Op. 53**

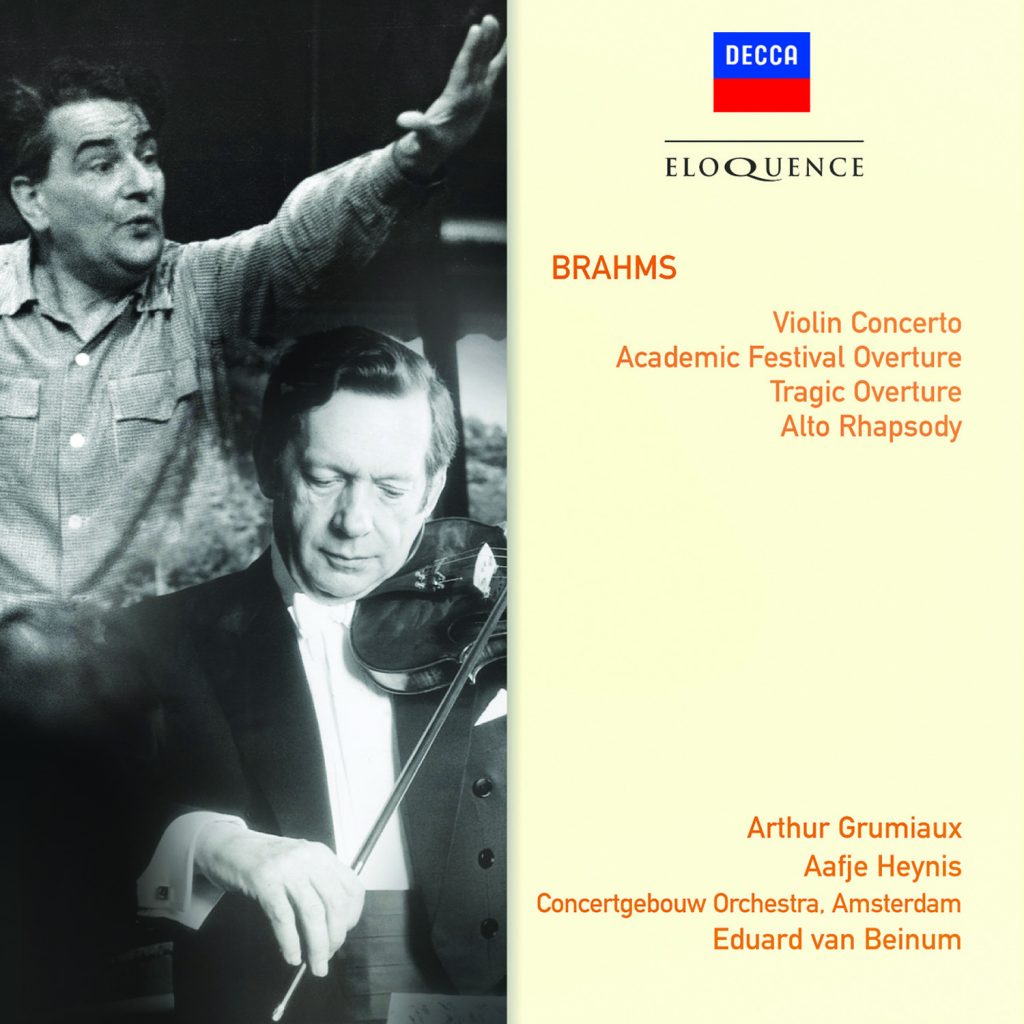

Arthur Grumiaux, violin*

Aafje Heynis, contralto**

Royal Male Choir ‘Apollo’**

Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam

Eduard van Beinum

Recording producer: Jaap van Ginneken

Recording engineers: Henk Jansen, Kees Huizinga, Willem van Leeuwen* (*Concerto, Overtures)

Recording locations: February 1958 (Alto Rhapsody); July 1958 (Violin Concerto), September 1958 (Overtures)

‘Simply put, Grumiaux’s 1958 recording of the Brahms concerto is superb… With an hour and a quarter of excellent music-making, intelligently coupled and priced at the bottom of the market, how can you possibly pass this up?’ MusicWeb

‘Highly recommended’ Fanfare

‘Grumiaux is on superb form in the concerto: this is an immensely cultivated and refined reading…The Academic Festival Overture is ardent, rhythmically exciting and utterly compelling, as is the Tragic Overture. Finally, there is Heynis’s rapt, beautifully sung account of the Alto Rhapsody’ International Record Review