Rachmaninov was so horrified by the disastrous 1897 premiere of his First Symphony that he became ‘a changed man,’ to use his own words. For two years after that fateful evening, he composed almost nothing, and occupied himself by conducting operas in Moscow and by concertising at home and abroad. The trauma caused Rachmaninov to develop what might be called ‘composer’s block’. How he overcame this psychological affliction and composed his Piano Concerto No. 2 – possibly the most familiar and beloved of all piano concertos – has long been a favourite story for the writers of program notes. By late 1899, his apathy had alarmed his friends to such a degree that they encouraged him to seek professional help.

Rachmaninov finally was persuaded to visit Dr. Nikolay Dahl, a Moscow-based specialist in hypnotherapy, and perhaps not coincidentally, an amateur musician of no small skill. Rachmaninov’s visits to Dahl began in January 1900, and continued on a daily basis for several months. Some writers have left the impression that the composer’s improvement was immediate, but such was not the case. Even as late as that June, he wrote to his friend and librettist Modest Tchaikovsky (the late composer’s brother) complaining that for the past two years he had ‘not composed a single note’ apart from a song. Modest had given Rachmaninov an opera libretto – ‘Francesca da Rimini’ – in 1898, and by June, Rachmaninov was about to give up hope of ever setting it to music. Perhaps confession really does free the soul because within a short time of writing to Modest, Rachmaninov had begun work on ‘Francesca’, completing the important love duet first.

Furthermore, he also began work on his Second Piano Concerto. The second and third movements were the first to be completed, and the composer was persuaded by his cousin Alexander Siloti to try the unfinished work out in front of an audience in December of that year. It had been eight years since he had played with an orchestra, he had caught a cold and he was understandably nervous that the farrago that attended the premiere of his First Symphony might be repeated. Fortunately, all went well, and Rachmaninov was able to complete the first movement of the new concerto the following April, and he premiered the entire work in October 1901, again with Siloti on the podium. (Today, Siloti is remembered more as a pianist than as a conductor, and indeed, he gave Rachmaninov’s new concerto its European premiere outside of Russia.) Unsurprisingly, Rachmaninov dedicated the work to Dr. Dahl.

The Piano Concerto No. 2 is one of those classical works which has spawned a popular tune – in this case, the song Full Moon and Empty Arms which is based on a theme from the concerto’s third movement. (Later on, Eric Carmen’s song ‘All By Myself’ was derived from the main theme of the second movement.) Typically for Rachmaninov, many of the concerto’s themes are structurally related to each other, although it is impossible to say whether this was intentional or simply a product of the composer’s subconscious. At any rate, these relationships give the concerto a cohesion and concentration unusual even for Rachmaninov.

Rachmaninov remained in Russia for another 16 years, finally leaving with his wife and two daughters a few months after the October Revolution of 1917. The forced departure of the Romanovs and the arrival of Lenin had irrevocably altered the composer’s homeland, and he no longer felt secure or able to work there. (In a later interview, he commented, ‘Only one place is closed to me, and that is my own country – Russia.’) The Communist regime confiscated whatever he had left behind, and Rachmaninov, short on money, soon realised that he temporarily would have to put his career as a composer to one side – playing piano concertos and solo recitals was more lucrative. For a time, the Rachmaninovs remained in Denmark, but by the end of 1918, they came to the United States. The composer spent much of the rest of his life in and around New York and California, and in Switzerland, where he built a villa he named ‘Senar’. (The first two letters correspond to his given name, the second two to his wife Natalya’s, and the last to ‘Rachmaninov’.)

In 1939, Rachmaninov completed an exhausting round of concerts in Europe, and with war threatening, he travelled back to the United States, where the Philadelphia Orchestra celebrated the 30th anniversary of his first arrival in that country with a series of concerts. With the same orchestra, he recorded his First and Third Piano Concertos – Eugene Ormandy was the conductor – and also his Third Symphony.

One last symphonic work remained to be composed, however. The Symphonic Dances were written during the summer of 1940 at the ‘Orchard Point’ estate near Huntington, Long Island. From the start, Ormandy had been Rachmaninov’s conductor of choice for the new work, and the composer even consulted him about the violin bowings he had written into the score. Originally, the work was titled ‘Fantastic Dances’ and there is reason to believe that the three movements originally were to have been titled ‘Noon’, ‘Evening’ and ‘Night,’ respectively. Rachmaninov never wrote a ballet, per se, but his ‘Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini’ had been choreographed by Mikhail Fokin, and the two men discussed whether the ‘Symphonic Dances’ might receive similar treatment. (In any event, Fokin died in 1942 and Rachmaninov in 1943, and nothing came of the project.) The work was premiered by Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra on January 3, 1941; the conductor was the dedicatee.

The ‘Symphonic Dances’ give a tantalizing glimpse of how Rachmaninov’s style might have developed, had he lived longer. The melodies are spiky (even Prokofiev-like), the rhythms are brusque, the harmonies are more subtle, and the diabolical half-tints of the ‘Paganini Rhapsody’ have been intensified. His scoring has become more refined and imaginative too – note, for example, the use of an alto saxophone in the first movement.

If there are hints of the future in this work, then there are also glances into the past. The ‘Dies irae’, the doleful Medieval plainchant that had been quoted or alluded to in so many of Rachmaninov’s works, makes one last appearance here in the final movement. At one point, he folds it into music reminiscent of a chant from the Russian Orthodox tradition. Later on, an actual quote from Rachmaninov’s ‘All-Night Vigil’ appears in the score, accompanied by the word ‘Alliluya’. Has eternal life triumphed over death? At the end of the score, Rachmaninov wrote ‘I thank thee Lord’. No doubt the composer was grateful that the composition of his last work – some, including Rachmaninov himself, called it his best work – went smoothly. On one level, perhaps he knew that he was approaching his own end. In that case, the words may be Rachmaninov’s thanks for a career – and a life – well lived.

Raymond Tuttle

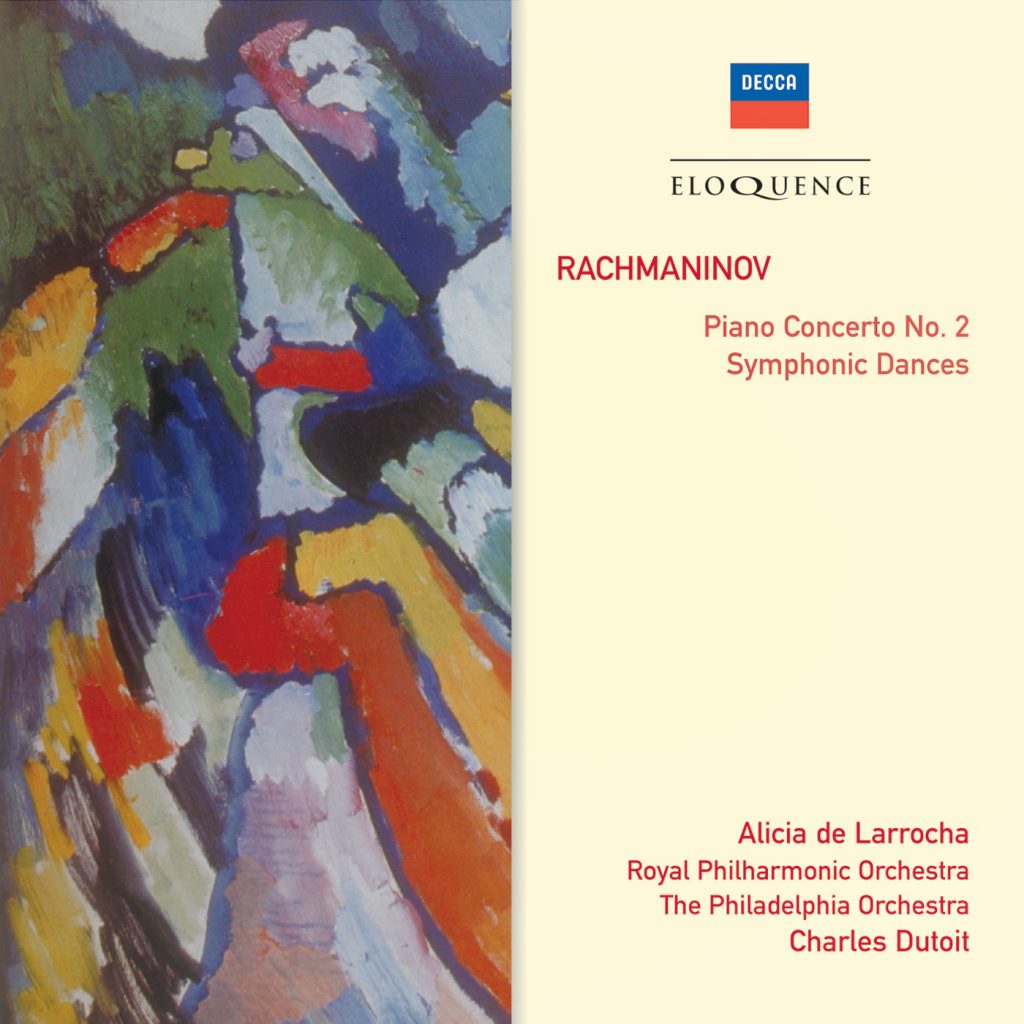

SERGEI RACHMANINOV

Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18

Symphonic Dances, Op. 45

Alicia de Larrocha, piano

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra [1]

Philadelphia Orchestra [2]

Charles Dutoit

Recording producers: Michael Haas (Concerto); Ray Minshull (Symphonic Dances)

Recording engineers: Simon Eadon (Concerto); John Pellowe (Symphonic Dances)

Recording locations: Kingsway Hall, London, England, September 1980 (Concerto); Memorial Hall, Philadelphia, USA, November 1990 (Symphonic Dances)

‘A luminous and moving account of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto … playing of exquisite beauty’ ClassicsToday.com