Reviewing and remembering our recording series for Philips with the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra has been joyous for me. Many thoughts and memories flood my mind and listening to them once again fills me with pride. Pride to have been given the opportunity to create a brand new orchestra; pride to work with a great recording company that entrusted me with choosing a new kind of repertory and creating musical journeys around certain ideas that linked like-minded music; pride to have worked with Anne Parsons, my true partner in creating the orchestra (she served as its first general manager) and subsequently Steve Linder, who then took over; pride to work with two former Yale students, Michael Gore and Tommy Krakser, who produced the albums (can there be any greater pleasure than to have students grow up and fulfill their promise in such a practical and real way?); pride in having an engineer (Joel Moss) who totally understood the sound we wanted for these recordings and who, together with my producers, afforded me the privilege of mixing the albums in the studio so that every aspect of the musical scores could be heard by our listeners. And throughout the journey, Mitch Hanlon was at my side to assist in our preparations and recordings.

I know. That’s a lot of pride, but it is really gratitude for being given the permission and privilege to work with those amazing and trusting people—starting, of course, with Costa Pilavachi who had me in mind to lead the new orchestra in the first place. And we certainly laughed a lot! Let’s look at some of the things I just mentioned.

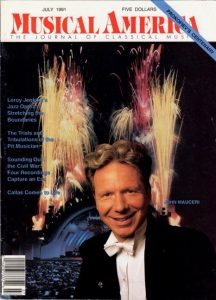

Blithely announcing at the press conference on the stage of the Hollywood Bowl in 1990 that the new orchestra would play the music composed in Los Angeles and that we would be “unafraid of being popular,” the gauntlet was dropped. Within a year, Decca’s Michael Haas began the Entartete Musik series in Berlin and invited me to be one of its two principal conductors. (Michael had traveled to Glasgow to meet me, knowing me only as the conductor of the My Fair Lady recording included in this compilation. I was conducting Scottish Opera’s first-ever production of Alban Berg’s Lulu, which completed a picture of my work and my rather catholic tastes.)

The learning curves for the Berlin series and the Hollywood/Los Angeles series resulted in the extraordinary discovery that most of the “Hollywood” composers of its first decades were in fact refugees from Europe whose names were also on the list compiled by the Third Reich as “degenerate.”

It is therefore no coincidence that the first track on the HBO’s first album, “Hollywood Dreams” is a fanfare by Arnold Schoenberg, written for Leopold Stokowski in 1945 when Stokowski was conducting the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra. It had never been recorded, nor had it ever been played! (Similarly, it is particularly apt that this compilation includes one of my Entartete Musik series, “Schoenberg in Hollywood” recorded in Berlin.)

Hollywood Dreams

That first Bowl album specifically included music composed, arranged, and influenced by Los Angeles’s unique cultural history, and includes music by Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Schoenberg, along with Max Steiner, Leonard Bernstein, John Barry, and John Williams. In other words, the gamut. This release included the first-ever modern recording of music from Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s mini-symphonic portrait of his score to The Adventures of Robin Hood, a suite from Herbert Stothart-Harold Arlen Wizard of Oz—both of which were Oscar winners—and the concert overture to Alfred Newman’s How to Marry a Millionaire—for which newly copied orchestral parts had to be created. I am particularly happy with our recording of Waxman’s A Place in the Sun in a version the composer had made for the Hollywood Bowl in 1963. Here, I felt, the ruminative adagios of Mahler met the sounds of a cocktail lounge—a perfect representation of its composer, trained in Dresden and Berlin, and who played in a German (Jewish) jazz band—Weintraub’s Syncopators—and was forced to emigrate to America. Reviewing this album thirty years later, what seemed logical to me at the time was revolutionary in 1991. No orchestral album had ever (to my knowledge) erased so many fake barriers to portray the continuity of 20th century orchestral music that emerged from Los Angeles, AKA “Hollywood.”

Ernst Korngold (left) and members of the Korngold family onstage at the Bowl after hearing music by Erich Wolfgang Korngold for the first time in 1991. [Photo: Donald Dietz]

Gershwin in Hollywood

This second album was the idea of Tommy Krasker and the casting of Patti Austin and Greg Hines was Michael Gore’s. As a musicologist, Tommy led us into the forgotten filing cabinets of RKO where photocopies of scores that had only been played once, in the 1930s, were kept. Finding the arrangements made by Johnny Green during the months after George’s death in 1938 was another hunt and gave us the solos and duets. To this day, the “Manhattan Rhapsody” and “Watch Your Step!” remain unique recordings. I find the last track, “For You, For Me, For Ever More” deeply moving.

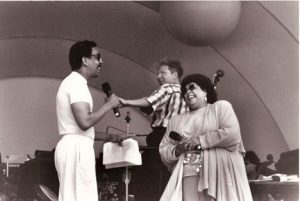

Gregory Hines and Patti Austin rehearsing for our Gershwin program in 1991. [Photo: Donald Dietz]

The Great Waltz

One of the curious byproducts of the development of popular dance in the 20h century was the waltz being supplanted by American music, beginning with ragtime. The waltz not only became outdated, it became symbolic of a genteel past. Beginning with Richard Strauss in his Der Rosenkavalier (1910) and Ravel with his La Valse (1920), new waltzes continued to be composed with great success in Hollywood, at first by the European refugee composers (Steiner, Waxman, Korngold, etc.) but continued with the next generation (Bernstein, Sondheim, Hermann). This album celebrates that continuity, beginning and ending with composer Dmitri Tiomkin’s mad Russian American arrangement of melodies by the waltz king, Johann Strauss, Jr., in the 1938 biopic The Great Waltz—composed when Austria fell to the Nazis. With the encouragement of Stephen Sondheim, my colleague David Gursky and I created “The Night Waltzes,” a symphonic work based on the melodies of Sondheim’s A little Night Music, while also referencing Rachmaninoff and Ravel, works the composer loved. Giving Fritz Loewe’s music to Gigi an airing within the framework of Der Rosenkavalier means the listener can hear how Conrad Salinger’s orchestration of the Gigi waltz references the French horns of Richard Strauss, and the recording of the monumental and La Valse-inspired waltz from Madame Bovary marked the first time that ailing composer Miklos Rozsa, well in his eighties, attended our sessions to hear music he had recorded in the very same room in 1949. If you listen carefully, you will hear a small voice say, “Bravo!” as the last note fades away. Rozsa, in a wheelchair, was blind and could not see that the red recording light was still on. We kept his comment in as a document of this historic moment. Collaborating with my colleagues in the mixing room made our recording of La Valse a particularly apt example of how a recording can represent Ravel’s orchestrations in both a specific as well as a warm acoustic.

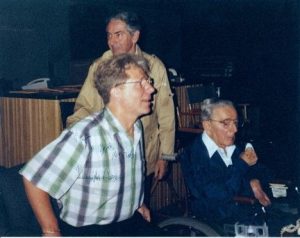

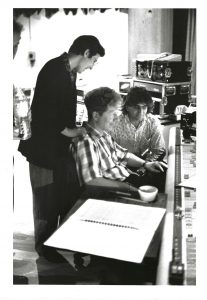

Miklos Rozsa’s autographed photo (with Tony Thomas behind him) at the recording session for his Madame Bovary Waltz.

Hollywood Nightmares

The sequel to our first album created an orchestral journey/concept album that was one of our hallmarks. With the scratchy sound of an early synchronized soundtrack to a silent film version of The Phantom of the Opera we did a “take down” of the music, so that the listener (“Don’t be afraid”) steps through the mirror. Accompanied by the Bowl Orchestra and in full state-of-the-art sound, the listener enters the dream world of our fears, beginning with Steiner’s 1933 music to King Kong, arguably the gateway score that proved that audiences would accept the sound of a symphony orchestra to underscore a drama. No one was asking why there was an orchestra on Skull Island, but they certainly understood the terror evoked by the three-note leitmotif that represented Kong, and the miracle of how Steiner turned those same three notes into a love theme of unfulfillable longing. The album explores various physical and psychological fears and can be heard as a single piece of music, with the last chord of Kong as the first chord of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring excerpt. Why Rite? The answer is that for all the history that tells us how important that work was in 1913, its global impact came from Walt Disney and Leopold Stokowski’s use of it in the 1940 Fantasia—when its unacceptable original story of a teenage girl being sacrificed to the god of Spring was replaced with the creation of the universe and ending with dinosaurs. The terror of this track is relieved by the resolution of John Williams’ chorale from his score to Jurassic Park—which, in its own way, provides a very different ending from the one Stravinsky gave the world in the years before World War I.

Hollywood Nightmares also gave us the opportunity to restore John Williams’ then-forgotten music to Dracula, explore the monumental music to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Franz Waxman—both terrifying and ultimately uplifting—Herrmann’s Vertigo, Barry’s musical evocation of a sexual nightmare in his Body Heat, Goldsmith’s homage to Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex in his music to The Omen, and best of all, Rozsa’s Spellbound Concerto with Stephen Hough as our soloist. Once again, Dr. Rozsa was in the studio, sitting just behind Stephen. It would be difficult to describe the power of his presence, so physically diminished, and yet the real maestro in that room.

Philips permitted us to hire a full chorus for the tracks that required them, allowing us to save the listener at the midnight hour with the glorious choral ending to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. It also was the first time we used the techniques Waxman could use in his soundtrack to tell its story on a recording—specifically that happy polka music in the pub between the murders. That the murder leitmotif predates John Williams’ theme for Jaws was another example of the continuity of the lexicon of music carried forward throughout the last century.

With John Waxman at MGM/Sony scoring stage. [Photo: Donald Dietz]

Heatwave

Unlike Gershwins in Hollywood, Philips called this album “Patti LuPone sings Irving Berlin,” which set up an expectation that it was a purely vocal album. And unlike the Gershwin album with its wonderful cartoon image of the Bowl designed by Chris Pullman, they put a photo of Patti in pink chiffon on the cover. Philips clearly wanted a pops orchestra and I wanted a popular orchestra that had a very different artistic goal. Nevertheless, with the help and leadership of Tommy Krasker, we created a musical portrait of one of Hollywood’s first visitors from Broadway, with Patti as a soloist among orchestral suites and restorations. Hiring the great orchestrator Sid Ramin to write the opening overture, starting with Patti’s wistful rendition of “There’s No Business Like Show Business” leads the listener into the world of Irving Berlin, much as the voice of the Phantom led the listener into the world of dreams and nightmares in the previous album. Once in Berlin-land, the album includes Tommy’s arrangement of “Let Yourself Go” leading into “Steppin’ Out With my Baby,” and the tour de force of “Best Thing for You,” “Lonely Hearts,” and “Always.” I created a dance suite from the film version of Call Me Madam and made the first recording of Steiner’s arrangement of Berlin’s “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” which became The Monte Carlo Ballet. Echoes of King Kong and pre-echoes of Casablanca infuse the symphonic variations of Berlin’s dark melody that accompanied one of the great dance sequences of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Follow the Fleet. Patti sings us to sleep at the end of this beautifully produced album.

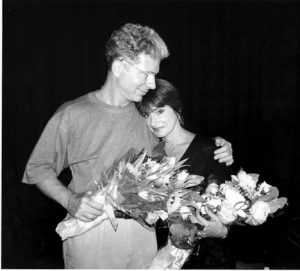

With Patti LuPone after one of her many concerts with the Bowl Orchestra. [Photo: D/ Dietz]

Opening Night (The Complete Overtures of Rodgers and Hammerstein)

Once again, Philips determined the album be called something that was incomprehensible to those of us creating it. Here, for the first time, was a complete one-of-a-kind traversal of all the Rodgers and Hammerstein shows in their Broadway orchestrations, and in chronological order. We added an overture by Sid Ramin to State Fair, which was the only original R & H film score (and which did not have an overture). Sid’s accomplishments on Broadway included creating overtures, like the one he wrote for Gypsy. Because The Sound of Music began without an overture, we included its entr’acte and went to William Brohn, who had worked with the show’s original orchestrator Robert Russell Bennett, to affix “Climb Every Mountain” to give both the entr’acte our album a terrific ending.

William Hammerstein said, “You have done us a tremendous favor,” and Dorothy Rodgers and daughter Mary were clearly moved to hear the little-known overtures, music they had not heard in decades. The liner notes designed by Christopher Pullman are some of the most imaginative ever produced for a CD.

Journey to the Stars

Inspired by a comment that Costa Pillavachi made that our recordings were “journeys,” I came up with the idea for this concept album. Linking each track of symphonic music, we got permission from MGM to use excerpts from the first purely electronic film score (Forbidden Planet 1956), composed by a woman (Bebe Barron), as well as electronic music from the Swedish Karl-Birger Blomdahl, whose 1959 opera, Aniara, takes place in a spaceship. After each electronic interlude, the listener “lands” in a different alien soundscape as portrayed by a composer of symphonic music.

We wanted to make the first studio recording of Ligeti’s Atmospheres used in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001—A Space Odyssey in 1968. The film’s soundtrack, performed by the Southwest German Radio Orchestra conducted by Ernest Bour, made the work famous, but a new recording, making use of all we had learned, seemed called for—especially in light of this context, which included contemporary “modern” composers. The Bowl orchestra, it should be said, played every note precisely as notated and the results remain impressive.

Mrs. Arthur Bliss gave us permission to create a suite from her late husband’s masterpiece to the 1936 Things to Come, which had been a favorite of mine as a child watching television, and John Waxman helped us create the “Creation of the Female Monster,” which includes some sound effects from his father’s 1935 score to Bride of Frankenstein.

The tintinnabulation of the electronic crystals from Aniara that ends the album is meant to calm the listener into finding beauty in alien worlds. For me, it will always be magical since I chose it to accompany my wife down the aisle in 1968—and we’re still married today.

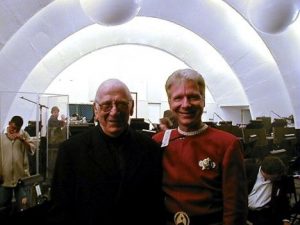

With Jerry Goldsmith in 2001.

The King and I

Dreams—Hollywood dreams—do occasionally come true. It was Michael Gore’s idea to ask Julie Andrews to record the role of Anna for a recording of the Rodgers and Hammerstein masterpiece. Here was a role she should have performed, but never did. My input was to use the film orchestrations made for Fox in 1956 and not to simply record the songs but to tell the story making use of the underscore. Thus, (another journey!) a listener could skip from song to song or experience the entire recording as a single narrative piece of music. The genius of Alfred Newman, Head of Music at Fox, was to take Rodgers’ melodies and use them as Wagnerian leitmotifs to tell the audience what was going on behind the spoken words and between the songs.

The rest of the cast is equally spectacular. When Julie met Ben Kingsley for the first time, it was electric, and all of us were able to call in our friends and colleagues to join in the recording sessions, including Ben whose son, Edmund, plays Anna’s young son, Louis. In the years that have followed all of us who participated in this album feel the joy we experienced each day. Blake Edwards, Julie’s husband, said it perfectly. “You were all in a state of grace.”

Songs of the Earth

Although Philips rejected the first title (Equinox) because “no one knows what that means,” and rejected the second title (Earthday), not sure why, the marketing team came up with a title that made us crazy, since it refers to a Mahler symphony and there are no songs in the album. That said, they released it, but as a pops album.

Here we are two decades later, and it is one of our proudest and wildest experiments for any kind of orchestra, especially a “pops orchestra.” The idea was to create a tone poem that celebrates the one cycle every living thing experiences on planet earth through the musical lens of symphonic composers. Like other albums, it can be enjoyed as individual works, but is designed to be experienced as a totality. Only one work comes from a film score, the tone poem by Franz Waxman that he created from his post-World War II melodrama Night Unto Night, in which an electric violin solo represents the spirit of a widow’s husband killed in the war. The work, called “Dusk” is another example of how German-trained refugee composers in Hollywood continued and expanded the classical music lexicon of Wagner and Mahler in the mid-20th century.

The fact that Philips permitted us to make this record still astounds me, no matter what they wanted to call it. I am particularly proud of the restoration of Stokowski’s Tristan love music. Leonard Bernstein had told me that every musician of his age learned the “sound of Wagner” from Stokowski’s records. That I assisted Stokowski when he was 90 and I was 27 made the work on this glorious transcription a joy. Because of the superb musicians in the orchestra, we separated the first and second violins, left and right, so the listener can hear how they call and answer each other. In mixing the album, we were careful to preserve every rapid note in the woodwinds for the Ravel dawn and brought the chorus forward with each of its entrances so that the listener got ever closer to the sun as it rose. For the finale, a second dawn, we chose the most epoch dawn in classical music, the dawn from Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder which requires 150 instrumentalists and a massive choir. We recorded members of the Los Angeles Master Chorale separately and re-recorded them over themselves twice so we could achieve the sound of an immense choir but balance it with the orchestra. Joel Moss, our engineer, did a masterful job on this album. It was during a break in recording this second dawn that a man came up to me at MGM/Sony scoring stage and said, “Hi, John. I’m Larry.” It was the composer’s son.

With Lawrence Schoenberg in his home.

American Classics

The simple idea was to record four American works from the era when “American” music became uniquely American and continue into the last quarter of the 20th century. The listener, therefore, can take this journey with us. Today, I am struck with the warmth and clarity of these extremely difficult-to-play but easy-to-love works. Ellington’s Harlem required some editing from various scores and careful attention to his own recording. Ellington’s colleague and orchestrator, Luther Henderson, was both kind and supportive of our recording. Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was my home territory. While Bernstein was alive, he permitted me to use his set of orchestral parts whenever I performed it. Together we had rooted out more than 100 errors in the original parts and now, two years after his passing, I had the honor of recording this beloved work with the man who had orchestrated it with Bernstein, Sid Ramin, at my side. John Adams’ The Chairman Dances is one of his most delightful and energetic pieces. Like our earlier recordings, whenever we could achieve a better recording, we used technology. In order to play the motoric sections and be totally accurate, we made use of a click track to give the orchestra an inflexible pulse, something the orchestra was accustomed to, but turned off the click for those sections that require freedom of tempo and expressivity.

Prelude to a Kiss

I had spoken to Ella Fitzgerald about returning to the studio and singing with a symphony orchestra which struck her a something “that would be fun.” Alas, this was not to be. Philips brought in a jazz producer, Robert Sadan, who took control of what and how we played, moving the orchestra to Paramount and bringing in his own soloists and featuring his own frequently non-tonal arrangements as well as pre-recorded percussion tracks. It was not a happy experience for anyone, including our soloist, Dee Dee Bridgewater, but I am happy that we got to record Ellington’s Night Creature, though Sadan added a 20-second improvised introduction at the top of the piece.

Always and Forever

Philips had clearly felt the Bowl Orchestra’s albums needed to be more commercial. After all, we were created in part to fill a niche in their catalogue that had previously been filled by the Boston Pops—which, given our goals, we were not. Another producer came in, Bob Belden, and together we created an album of love music. Sixteen tracks of shorter pieces made for a voluptuous traversal of Hollywood music—confronting “modernism” as the other side of the coin in 20th-century symphonic composition. Guest soloists sprinkled the album, and it was lovely to work with each of them. Although this album was something of a throwback to our “Hollywood Dreams,” it did allow us to play some wonderful music. Continuing our tradition to use modern technology, we took an amateur recording of Erich Wolfgang Korngold playing music from his 1947 score to the Warner Bros. Escape Me Never at a party and created an orchestral accompaniment based on the original cue in the film. Also, recording Miklos Rozsa’s “Eternal Love” from his very first Hollywood score (The Thief of Bagdad) a week after his interment was profoundly moving for the orchestra. I think you can still feel that when you listen to this magnificent love music. This recording was first heard in public on September 5, 1995, as the final event in Dr. Rozsa’s memorial service.

With Elmer Bernstein at the Bowl. His love music to The Age of Innocence was one of many works of his we performed. His last composition, “Fanfare for John at the Bowl” was composed months before his passing in 2004.

The Hollywood Bowl on Broadway

Our journey comes to an end with this release in which I wanted the Bowl orchestra to play long-form orchestral tone poems based on the music of Broadway. Rarely played in concert—because they would be too long for the condescending attitude toward “pops” audiences and too popular for “serious” concerts, this album confronts the walls that separate popular from serious to bring joy and discovery to the listener. Composer/arranger Morton Gould participated in the restoration and reformatting of his traversal of Richard Rodgers’ Carousel and the theater music of Kurt Weill. Hearing “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue” in the expanded symphonic arrangement by Hans Spialek who had made the original Broadway orchestrations of the work in 1936 brought back sweet memories of having worked with him in 1983 when Hans was 87. Tommy Krasker brought Arlen-Mercer’s Blues Opera to my attention—something that has led me to restore the entire opera with my colleague Michael Gildin, and as of this writing, it awaits its world premiere. And since Show Boat was perhaps the most significant Broadway musical of all time, we chose to end the recording with Jerome Kern’s magnificent “Scenario for Orchestra.” Show Boat first appeared on Broadway in 1927, and was the subject of three films and numerous productions. However, in 1941, Kern responded to a commission from the Cleveland Orchestra to create a purely symphonic retelling of its story. This work alone was worth the creation of this album. Perhaps it will be played again by orchestras and conductors who are unafraid of being popular by performing music that celebrates the American Song Book dressed up for a symphony concert.

Epilogue

The Hollywood Bowl Orchestra and what we attempted to do in the 1990s and up to 2006 when I stepped down, is a story of success and failure, perhaps in equal parts.

These recordings are truly experimental in what we played. In retrospect playing records that mix vocal tracks and purely orchestral ones might not have been a good idea. People listen differently to songs than they do to symphonic music. That Philips let us program classical

excerpts is also astounding. Does anyone really want to hear only “dawn” from Daphnis and Chloe? Yes, it requires a different commitment from the listener, but is nonetheless heretical to classical music lovers. That said, putting composers seen as separate into a larger continuum felt worth it then and worth it now. Thirty plus years later, these albums remain unique.

Of course, there was conflict with our ultimate boss, Philips, and these discussions usually focused on titles and cover art. Frankly, we did not sell enough albums to make the project worth it, despite consistent glowing reviews. That said, there are really few long-term recording commitments in classical music anymore and the orchestras that have them usually foot the bill as part of its marketing strategy for the institution and its music director. Listening again, these record sound expensive, and they were!

The other part of our lack of sales, however, was linked to Ernest Fleischmann, the executive director of the LA Philharmonic, who agreed to greenlight the orchestra in the first place. He needed us to be very much a support system for the Philharmonic. That he refused to allow our records to be sold at the Bowl was a source of tremendous frustration with our colleagues at Philips. And when you consider that we played to a combined audience of four million people over a sixteen-season run, that certainly could have made us the most successful orchestra in the world.

Anne Parsons and I knew about the internal snobbery of the Boston Pops players because they were also members of the Boston Symphony but minus their first desk players. There was always a sense that playing the pops was lowering one’s standards, and to be fair, the rehearsal conditions and noise levels of the Pops audience made the music making feel secondary to the experience of its audience. When I first conducted the Pops in the late 1970s, I entered the stage and no one in the audience took notice. Everyone was merrily chatting away, eating and drinking, and I asked the concert mistress, “Do they ever settle down?” to which she said, “Just. Start.”

That is why we did not permit any member of the Los Angeles Philharmonic to play as a member of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. We did not want it to be a rotating door of Philharmonic players who might play some weeks and not others. The solution was a brilliant one: have the great freelance players of the Hollywood studios, many of whom played in the LA Chamber Orchestra and in string quartets, be the members of the new orchestra.

Anne Parsons with Joel Moss at the mixing console. [Photo: Donald Dietz]

The Philharmonic needed the HBO to be successful, but not too successful, because its mission, understandably, was the Philharmonic. At first, we filled in the weekends that had been negotiated in the Philharmonic’s 1990 contract that gave them some weekends off and the subscribers, as far as we know, never complained that we played on their subscription. There must have been a series of internal debates about us. On the one hand we were playing to sold-out houses—on some weekends, after a Sunday night was added—we might have 54,000 people and the top price of tickets was $250.00. On the other hand, the Philharmonic’s players and its administration must have wanted to focus its attention on its brand and not on the “spin-off orchestra” as the New York Times referred to us in 1990. Our tours were cancelled, and our recordings stopped. The Philharmonic began playing the HBO repertory: operas, dance, and most surprising of all, movie nights that featured live-to-picture performances—something the Philharmonic had avoided for its entire existence with the unique exception of its commitment to John Williams. In that sense, our mission has been accomplished and this Decca release has reminded the world of the work so many of us did thirty years ago. For this, I am profoundly grateful.

John Mauceri

Founding Director

Hollywood Bowl Orchestra

December 4, 2023

All photos provided by John Mauceri, unless otherwise stated.

Order The Sound of Hollywood here.