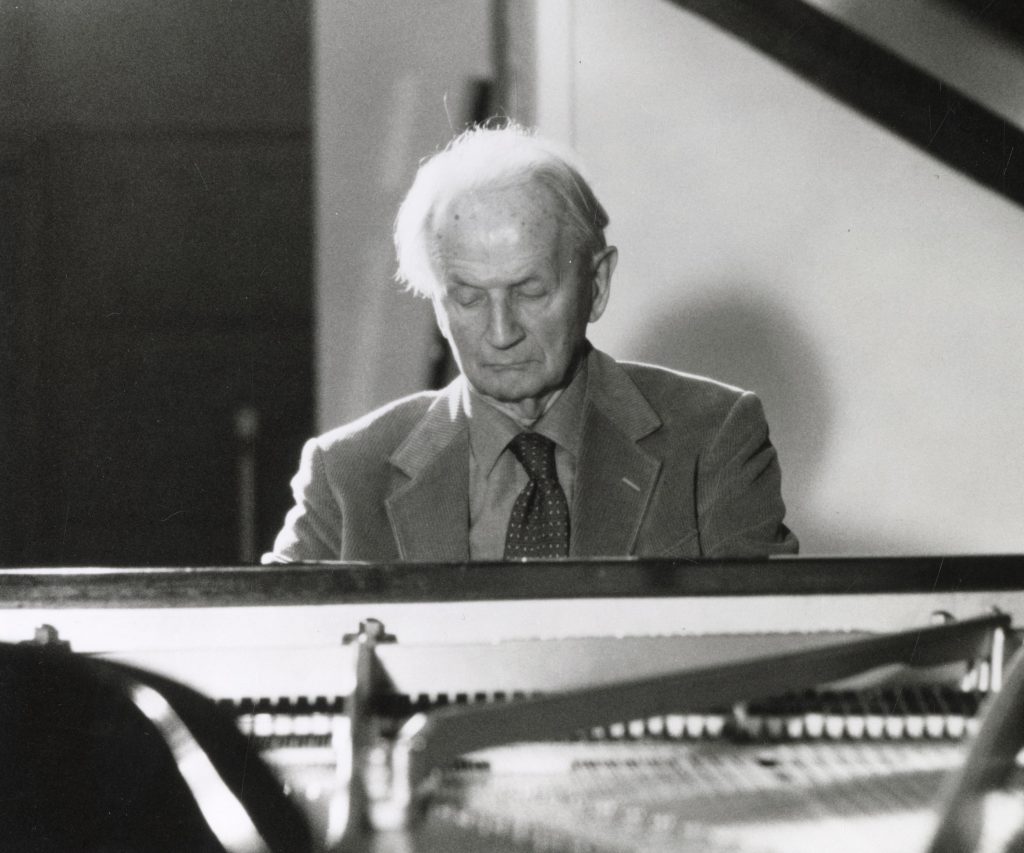

MICHAEL GRAY explores the Wilhelm Kempff legacy

Wilhelm Kempff began recording for Deutsche Grammophon (DG) in the autumn of 1922. (Kempff is quoted as saying he began recording in 1920. However, his first record falls within DG’s matrix series for discs made in the autumn of 1922.)

Before 1916, DG had been the German branch of The Gramophone Company. Now it was German-owned and was building a new catalogue following the wartime hiatus and divorce from its former British owners. Other pianists had recorded for Grammophon before 1914, and Kempff was not the first pianist to make records for the ‘new’ DG – an honour which had fallen to Eugen d’Albert (1864–1932) in 1918. Kempff’s 1922 debut disc (62400) presented Beethoven’s Bagatelle Op. 33, and his Ecossaises – which was the first recording of the original text. Four sides of Bach followed in the spring of 1923, including a transcription by Kempff of the Sinfonia to Bach’s Cantata No. 29. All of these were recorded premieres, suggesting that the old repertoire of opera and operetta arias and salon pieces would belatedly begin to expand and encompass hitherto unrecorded works by ‘The Three Bs’: Bach, Brahms and especially, Beethoven.

Isolated movements from Beethoven’s piano sonatas had been preserved on acoustic records as early as 1908, though by the 1920s, all 32 sonatas had already appeared on piano rolls. Realistically recording the piano was difficult via acoustic apparatus, which was not tuned to the sound of hammers hitting strings. Dynamics were entirely at the discretion of the performer, who had to make adjustments to convey a convincing contrast between forte and piano in spite of the limitations of the acoustic process.

These were the challenges faced by Kempff (and the engineers) when he again went before DG’s acoustic recording horn in the spring of 1924, setting down a total of 28 sides. The repertoire included seven Beethoven Sonatas, four of which (Opp. 13, 26, 81a and 101), were new to gramophone records. By 1926, Kempff had recorded two-thirds of the Beethoven sonatas then in the European catalogues.

Kempff returned to the Grammophon studio in September 1925 to record Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto with members of the Berlin Staatskapelle (no conductor is named on the labels). Although DG had begun to make records using American Brunswick’s ‘Light-Ray’ process as early as March 1925, these acoustically inscribed sides were the pianist’s final recordings using the old and now passé system.

Kempff’s first recording with the new ‘electrical’ process in 1926 produced just three works, which included Beethoven’s Op. 90 Sonata. During the next two years, however, there followed a flood of discs that used a new process known as ‘Raumton’, which simulated a concert-hall perspective missing from DG’s old acoustic and first electrical records. These records from the spring of 1927, recorded in the auditorium of Berlin’s Hochschule für Musik, included a quartet of ‘named’ Beethoven sonatas – Opp. 13 ‘Pathétique’, 27 No. 2 ‘Moonlight’, 53 ‘Waldstein’ and 57 ‘Appassionata’ – plus second versions of Op. 26 and Op. 81a ‘Les Adieux’. In the autumn, Kempff returned to the Hochschule to repeat sides of the ‘Pathétique’ and the ‘Moonlight’. By the spring of 1928, all six newly recorded sonatas were being sold as part of DG’s Beethoven-centenary celebrations.

Kempff returned to the studio in the spring and autumn of 1931 to make further versions of the Sonatas Opp. 26, 27 No. 2, 53 and 57, while adding a first recording of Op. 78. These new records, evidently the result of improvements in DG’s recording technique, were again made in the Hochschule’s concert hall. When issued in the spring and summer of 1932, they garnered praise from reviewers throughout Europe and the US. Even so, with the collapse of the German music industry and precipitous fall in DG’s sales, it would be almost four years before Kempff recorded again. By then, his art had become well-known and admired outside Germany via records exported under the Polydor trademark, and from discs manufactured from Grammophon masters by American Brunswick and British Decca. Thanks in part to his recordings, he had begun to tour in Europe and South America as a musical ambassador of the new Germany’s cultural achievements.

Kempff returned to the DG studios in May 1935, now with an exclusive contract, to partner the violinist Georg Kulenkampff in Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata. Further solo sessions in July at the Kino-Saal studio produced recordings of Mozart’s Sonata KV 331, plus works by Schubert, Schumann, Schubert/Liszt, and Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 31 No. 3. The following year, he recorded Beethoven’s Op. 69 Cello Sonata with Austrian cellist Paul Grümmer. Aside from two Mozart recordings made in August 1941, Beethoven remained the focus of his recording activity until after the war.

As with most artists entangled with the Third Reich, Kempff’s post-war career did not resume immediately. His old record label was recovering from destruction in Berlin and was focused on rebuilding its catalogue with other artists. The pause afforded Kempff an opportunity to concentrate on composing, but with recording on temporary hold at home, Kempff needed to find another label. That label turned out to be DG’s old British partner, Decca Records. Decca’s Continental representative, Maurice Rosengarten, had already signed the veteran Wilhelm Backhaus, and it was Rosengarten who threw a recording lifeline to Kempff.

Decca did not enjoy the prestigious pianistic roster of some of the other major labels in the 1930s and 1940s. While world-class pianists customarily appeared on Victor, HMV and Columbia, Decca relied on artists who enjoyed worthy but strictly local celebrity, with the notable exceptions of British pianists Kathleen Long, Clifford Curzon, Moura Lympany, and Australian Eileen Joyce. Following World War II, Decca began to enlarge its stable of keyboard artists, taking on American Julius Katchen in 1947, bringing Clara Haskil to London to record in July 1947, and Friedrich Gulda to the West Hampstead studios in October 1947. Katchen remained with Decca until his death in 1969 and Gulda was a prolific recording artist for Decca before he left the label in the autumn of 1958 with a final spurt to complete a cycle of Beethoven’s piano sonatas.

In July 1950, Backhaus made his first Decca recordings at the Victoria Hall in Geneva, of Beethoven sonatas and music by Chopin. Kempff, however, had begun recording in Decca’s West Hampstead studios a few months earlier, in October 1949. There he made several 78rpm sides, issued together as K28223–26. Bach’s Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue occupied three of them; others were devoted to his own Bach transcriptions, none of which he had recorded before.

In March 1950 he was back at the Decca studios recording Brahms’s solo piano works for the first time, the cycle continuing in sessions across 1953. LX 3033, a 10” containing the Op. 79 Rhapsodies and Op. 117 Intermezzi did not last on the shelves, with Kempff re-recording them in 1953. They received a brutal review from Lionel Salter in the July 1951 issue of The Gramophone, beginning ‘I just don’t know how this recording came to be passed for issue’. He goes on to criticise the seemingly appalling quality of the recording, and ends his review saying ‘For an artist of Kempff’s stature this is a lamentable issue’. Perhaps it was the quality of the pressings Salter had at hand, as the original tapes which have been remastered for this issue do not contain the various issues Salter points out.

By this time, Decca had begun to record on magnetic tape with the aim of launching LP records in the UK in June. As a result, only two items from Brahms’s Op. 118 were issued on 78rpm discs; everything else appeared on two 10-inch albums (LX 3032 and LX 3033). As reviews of LX 3033 attest, the transition from 78 to EP and LP was not always completely successful. Further sessions in November at the West Hampstead studios shifted Kempff’s attention to Schubert (the great B flat major Sonata – another first recording for him) – and works by Liszt, including the two Légendes. The Schubert and most of the Liszt from these sessions were the last recordings of Kempff to be issued on Decca 78rpm discs.

Kempff’s contract with Decca was non-exclusive and allowed him to record for other labels. In December 1950, he was back in the studio, not in London, but in Hanover’s Beethovensaal, where DG had relocated its piano recording activity. The repertoire, the Pathétique and Moonlight sonatas, opened a new chapter in Kempff’s career with a second cycle of Beethoven’s piano sonatas which was completed during the following year.

During 1951, and until his final sessions for Decca in February 1958, Kempff alternated between making records in London and Hanover. This unusual arrangement benefitted both companies. Decca could build a catalogue of German masterpieces performed by an experienced and acknowledged master. Meanwhile DG secured the same mastery in the sonatas and concertos of Beethoven, and later on in music by other German composers.

Having been known to British audiences only through his recordings, Kempff made a belated debut at London’s Wigmore Hall on 27 October 1951, and he stayed in the English capital to record Liszt’s Petrarch Sonatas and Schumann’s Arabeske and Papillons for Decca. He made no recordings at all during the following year.

In May 1953, he embarked on a new cycle of Beethoven’s piano concertos for DG with the Berliner Philharmoniker under Paul van Kempen. Two months earlier in London, he had recorded Schubert, remade Bach’s Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, and a set of his own Bach transcriptions, all at Decca’s West Hampstead Studios, and made his first recording of Schumann’s Piano Concerto. In October, he made his only record at the Victoria Hall, with two Mozart concertos (Nos. 9 and 15) which were new to his discography, accompanied by the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra and the Winds of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande under Karl Münchinger. He ended the year by making three Decca LPs of short works by Brahms, from Op. 10 to Op. 119, completing the series he had begun in March 1950.

Kempff spent one day in May 1955 in London recording short pieces by Couperin, Rameau, Beethoven and Handel, a session that that yielded three 45rpm discs. He was absent from Decca’s studios for the following two years. While in Hanover during 1956 and 1957, he was occupied with Schumann, the Handel Variations by Brahms, and a remake of Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight’ sonata.

In 1941, during a visit to German-occupied Paris, Kempff was asked in a newspaper interview which composers he preferred above all others. He cited Bach, Beethoven and Mozart in his reply, all of whom he had recorded or would soon record for DG. The final member of the quartet was Chopin, whose works he had played in concert, but had never recorded. He finally made amends for that omission over four days in February 1958: his first stereo sessions and his last for Decca, yielding three LPs of Chopin’s music. The following month, he was back in Hanover recording Brahms, and he never returned to Chopin in the studio. His final recordings were made in Hanover by DG during his 79th year, the culmination of a long and distinguished career on record.